Genting’s Singapore promise as LVS gears up

The ‘righteous’ elements of Singapore’s media have been working hard to highlight the dark side of the itystate’s first ever casino, which opened its doors to the public on 14th February—the first day of the Chinese New Year.

One of our favourite headlines, ‘Resorts World Sentosa visitors ogle at scantily-clad showgirls,’ appeared in the aptly named Sin Chew Daily, and concluded, “The entertainers with revealing outfits had the men glued to their chairs and they decided not to gamble.”

Disregarding the ambiguous grammar (‘they’ could suggest it was the entertainers who decided not to gamble, and rightly so), the report fails to explain how the casino managed to generate an estimated US$7-8 million a day in the “last week-or-so” of February, according to a note from Las Vegas-based Union Gaming Research, which did not disclose its undoubtedly impeccable source. These figures follow initial revenues in the US$3 million a day range.

The opening-day crush of mass-market curiosity seekers—with crowds exacerbated by the Chinese New Year holiday—must have kept serious gamblers away during the first few days of operation. Furthermore, as explained in “Claw Back” in the last issue of Inside Asian Gaming, Chinese New Year in Macau is characterised by increased mass market casino visitation, while VIPs action is down, presumably because high rollers are either home with their families or off to Las Vegas. The same should hold true for Singapore. Union Gaming Research noted the figures for end-February were split fairly evenly between VIP and mass market, whereas the initial figures were in likelihood dominated by the mass market.

Though the RWS casino is still very much basking in its new property glow, the US$7-8 million a day revenue figure is impressive. Union Gaming Research observed: “To say these numbers are encouraging is a monumental understatement, especially without the influence of junket operators,” but warned that such numbers for RWS are not sustainable, given the upcoming Marina Bay Sands (MBS) opening.

Thank you CRA

RWS owes Singapore’s finicky Casino Regulatory Authority (CRA) a debt of gratitude for processing the licence application in time for the casino to open on the biggest holiday in the Chinese-speaking world—which this year coincided with St. Valentine’s Day.

The phased opening of RWS had kicked off on 20th January with the unveiling of four of the resort’s six hotels, but with the casino still waiting to be licensed—largely owing to the late filing of the complete licence application according to government sources. Many industry watchers speculated that RWS could be left standing with its finger on the casino trigger until March or April, losing much of the first-mover advantage it hoped to gain over MBS, which is scheduled to open on 27th April—though contractors involved with the project warn one more delay could still be on the cards. MBS, owned by Las Vegas Sands Corp (LVS), is the only other property licensed to operate casino gaming in the Lion City, and the Singapore government has vowed not to issue any further licences until at least 2015.

In January, a sea of pending licence applications swamped the CRA, extending beyond the casinos themselves to the licences for the games and equipment inside them. Squeaky-clean Singapore will vigilantly maintain a wall of red tape around its casinos in order to deter money laundering and to safeguard its position as a world-class financial centre. Given the need to adhere to regulatory standards more stringent than those of any major gaming jurisdiction, the CRA must have worked around the clock to process all the necessary licence applications in time for the mid-February opening.

Regulating away the junkets

Although the fastidious CRA has disproved cynics who claimed bureaucracy would reign and rob the RWS casino of its first-mover advantage, it appears Singapore’s casino regulator has robbed the two properties under its purview of any substantial junket business by effectively regulating away the junkets.

The CRA released its much-anticipated details on the licensing and regulation of junket operators on 31st December (the details are discussed in both the January and February issues of Inside Asian Gaming). While Macau’s junket operators could be lured to jump through the regulatory hurdles to get licensed in Singapore, the nail in the coffin of Singapore’s junket courting ambitions is the requirement that junket players identify themselves in advance of entering the casinos, which runs counter to the players’ strong preference for anonymity when going on gambling jaunts.

This has allayed fears that Singapore’s low 12% preferential tax on junket and ‘premium’ play (including the 5% levy on ‘premium play’—as opposed to the 15% levy on mass market revenuea—and the 7% goods and services tax) would enable its casinos to offer higher commissions to lure junkets from Macau, where all gaming revenue is taxed at 39% (including 35% as direct tax and 3-4% as mandatory social and welfare contributions).

Fine, young, but no cannibal

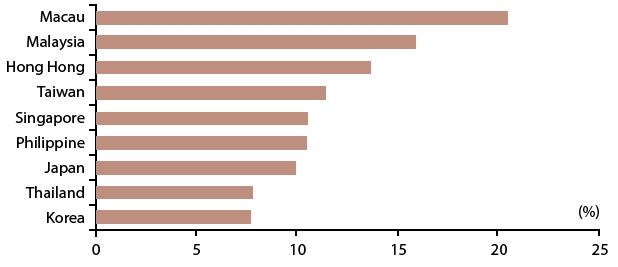

The consensus view from analysts now is that Macau will see very little fallout from Singapore’s casino openings. The following table highlights investment bank Merrill Lynch’s estimates for how much of a new casino gaming market will be created by the new Singapore casinos, and how much revenue will be cannibalised from major competing casino jurisdictions in the region.

Malaysia faces the greatest cannibalisation from the Singapore IRs at its Genting Highlands casino—Malaysia’s monopoly casino—which Merrill estimates could be cannibalised to the tune of US$202 million, or approximately 20% of its forecast US$1.1 billion gaming revenue for 2010.

Potential cannibalization amount |

||

| US$mn | 2010 | 2011 |

| Estimated Sg casino market | 1,900 | 2,800 |

| Cannibalization | ||

| Malaysia | 202 | 158 |

| Australia | 55 | 40 |

| Macau | 155 | 155 |

| Other markets* | 65 | 65 |

| Estimated amount Cannibalized |

477 |

418 |

| Potential new market |

1,423 |

2,382 |

| % Cannibalized | 25% | 15% |

| % new market | 75% | 85% |

| Source: BofA Merrill Lynch Global Research estimates | ||

| * mainly cruise ships | ||

The US$155 million cannibalisation forecast for Macau, on the other hand, is equivalent to just under 1% of forecast 2010 revenue. Merrill’s belief that the arrival of casinos in Singapore will have a limited impact on Macau is predicated on the continued dominance of junkets in the latter market.

VIP baccarat accounted for two thirds of Macau’s US$14.9 billion casino revenue in 2009, and of that, an estimated 90% was generated by players brought in by junket operators.

Junkets are indispensable to Macau’s VIP gaming trade because China’s currency controls prevent mainland Chinese high rollers bringing large sums of money out of the mainland into Macau to play with. Casinos are also reluctant to extend credit to mainland Chinese, since gambling debts are not legally enforceable in China. The casinos are happy to leave the junkets—which boast wide and influential networks across the mainland—to handle the extension and collection of credit to mainland Chinese.

Though Macau casino operators are boasting of increasing their proportion of direct VIP players relative to those brought in by junkets, direct players are still estimated to account for only 10% of all VIP players in the city. The junket players also account for disproportionately more turnover, according to IAG‘s junket sources, presumably because the direct players who do not have credit relationships with the casinos are limited by the funds they have physically brought with them, while junkets stand at the ready to extend more credit to the players they bring.

There is also the matter of geography, giving Macau and Singapore distinct and separate markets.

Macau boasted 21.8 million visitors in 2009, though the average length of stay in Macau is only about 1.4 days, compared to around 3.5 days in Singapore. Just over half of Macau’s visitors last year were from mainland China, another 30% from Hong Kong and about 6% from Taiwan. Thus, over 86% of visitors to Macau hail from Greater China, and of the mainland Chinese visitors, an estimated 80% come from just across the border in neighbouring Guangdong province.

Tourist arrivals growth between 2003 and 2008 |

|

Last year, Singapore’s tourist arrivals were down 4.3% year on year to 9.7 million. The casino-centred integrated resorts (IRs) have hopefully arrived just in time to halt the decline in tourism. Given the explosion of Macau’s visitor numbers since the opening of its first glitzy foreign operated casino in 2004, the IRs could indeed help the Singapore government achieve its objective of raising arrivals to 17 million a year by 2015.

Currently, Malaysia is by far the largest source of visitor arrivals to Singapore. It should be noted, however, that because Singapore’s visitor statistics only count arrivals by sea or air, they do not properly reflect the dominance of Malaysia as a source market. Approximately 9 million people cross the land border between Singapore and Malaysia each year, though a large proportion of them are likely to be day-labourers crossing over for work. In order for Singapore to get an accurate picture of the influence of casino resorts on its total tourism numbers it may need to start breaking down and reclassifying the land border arrivals.

The top five source markets for tourist visitors at Singapore’s air and sea borders in 2009 were: Indonesia (1,745,000 visitors), China (937,000), Australia (830,000), Malaysia (764,000) and India (726,000). Together, these 5 markets made up over 50% of arrivals to the city-state last year.

The bulk of Singapore’s casino patrons will consist of Malaysians and local Singaporeans. With a population approaching 5 million, Singapore is expected to generate considerable homegrown gaming demand, in contrast to Macau, where the half million strong population hardly makes a tangible contribution to casinos’ coffers.

The third largest source of players at Singapore’s casinos is expected to be Indonesia. Singapore’s casinos in particular will covet wealthy Indonesians. A report by consulting firm Capgemini shows there were an estimated 23,000 high-networth individuals (HNWI) in Indonesia in 2008, with total assets of US$80 billion. The report estimates that one-third of Singapore’s HNWIs are Indonesians with permanent-resident status, holding another US$80 billion.

Among the VIP players arriving directly (i.e. not via gambling agents) at Macau’s casinos are Hong Kong residents, Taiwanese and Southeast Asians, who are unrestricted by currency controls, as well as wealthy mainland Chinese with offshore companies and/or overseas bank accounts and assets. These direct VIPs probably collectively account for at most 6% of Macau’s casino revenue. Still, this does suggest that there is potential for more than 1% of Macau’s revenue to be cannibalised by Singapore, especially since Singapore is a regional business hub, and some of these players may find themselves already going regularly to Singapore.

Direct players will also be incentivised to take their business to Singapore. RWS is offering direct players a rebate of 1.1%, while direct players in Macau only get about 0.8%. Despite the higher rebate, RWS is still likely to achieve better margins on its direct players because of Singapore’s lower gaming tax rate.

Whereas junkets rule in Macau, the direct player is king in Malaysia. Merrill Lynch estimates 80% of rolling chip turnover in Malaysia comes from direct VIP players. Even if the CRA had not in essence regulated away the junkets from Singapore, RWS and MBS would likely have followed the Malaysian model of courting VIP players directly. In fact, if it weren’t for the irksome credit issue, even Macau’s casinos would junk the junkets, who are, after all, essentially middlemen taking a cut. LVS revealed in a June 2009 note to investors that its margin on direct high roller play in Macau was 1.0 to 1.2 times higher than the margin on players fed to it by junkets.