Can Singapore really cater for 80,000 conference visitors at its casino resorts?

The Singapore government’s rationale for introducing casinos to the city-state is well publicised and very clearly targeted. It wants to increase annual tourism to 17 million arrivals, compared to the 10.1 million recorded in 2008. It also wants to double annual receipts from tourism to S$30 billion by 2015, compared to the S$15.2 billion achieved in 2008.

‘International inbound tourism receipts’ are defined by the United Nations World Tourism Organization as “expenditure of international inbound visitors, including their payments to national carriers for international transport”. That definition includes local taxes. In Singapore’s case, that’s not only a 7% Goods and Services Tax on retail sales such as hotel rooms and restaurant meals, but also gaming tax and GST on any gambling they do in the city’s new casinos.

‘International inbound tourism receipts’ are defined by the United Nations World Tourism Organization as “expenditure of international inbound visitors, including their payments to national carriers for international transport”. That definition includes local taxes. In Singapore’s case, that’s not only a 7% Goods and Services Tax on retail sales such as hotel rooms and restaurant meals, but also gaming tax and GST on any gambling they do in the city’s new casinos.

When Lim Hng Kiang, Singapore’s Minister for Trade & Industry, first spoke publicly on the tourism revenue issue in April 2005, he avoided mentioning the potential gains from gaming tax. Instead, he stressed the need to reverse the declining contribution of tourism to the city-state’s gross domestic product and the need to support the city’s meetings, incentives, conventions and exhibitions (MICE) market.

“Tourism has always been an important sector for the Singapore economy and not simply for the tourism receipts that visitors generate. The more attractive we are as a tourism destination, the easier it is for us to develop our convention and exhibition industry, and grow as an aviation hub,” stated Mr Lim.

Singapore’s main fix for its tourism ‘problem’ is two new casino resorts. There are other, seasonal fixes, including the reintroduction in 2008 of the Singapore Grand Prix to the Formula One season. The race, held in the Marina Bay area, also has the novelty of being F1’s first regular night race. That, in its turn, virtually guarantees that many spectators book into hotels overnight. It’s clever stuff from the Singapore authorities.

Pricey admission

Meanwhile, back on the Asian casino circuit, Malaysia’s Genting Group and its consortium partners and Las Vegas Sands Corp have between them spent around US$6 billion on tourism infrastructure in Singapore—all for the sake of two precious casino gaming licences. That cash is equivalent to Brazil’s entire receipts from foreign tourists in the whole of 2008, according to figures given by Luiz Barretto, Brazil’s Minister of Tourism at the Global Travel and Tourism Summit in May 2009. The US$6 billion spent by the casino operators in Singapore is not, strictly speaking, free money for the Singapore government, given that opponents of gaming argue there is a social ‘cost’ connected with the industry.

But Asian casino licences nonetheless attract big premiums. Genting and LVS are doing it because they expect to make the money back many times over, given the proven propensity of Asians to gamble hard and often. Singapore offers the potential of not only ethnic Chinese customers from its domestic market, Malaysia, Indonesia and mainland China, but also Indian nationals—a wild but potentially lucrative card in the Asian gaming scene.

Analysts’ estimates of the size of the gaming component of the Singapore casino market vary somewhat. Anil Daswani, global head of gaming research for Citigroup Investment Research, forecasts Singapore’s two IRs will generate US$2.8 billion in casino revenue in 2011, their first full year of operation. Aaron Fischer, a senior analyst at investment bank CLSA, is more bullish, estimating US$3.5 billion revenue in 2011.

But there are key structural differences between the Singapore and Macau gaming markets, as Inside Asian Gaming has reported. On the upside, Singapore is a duopoly (if one excludes the role of Singapore’s slot clubs) within five hours flying time of half the world’s 6.6 billion people. And it’s the half that most likes to gamble.

Potentially on the downside, the Singapore casinos have relatively small footprints in relation to the total project (a maximum of 5% of gross floor area). That suggests producing good returns on the rest of the casino operators’ real estate will be even more important than it is in Macau.

Such is the strength of the gaming revenue stream in Macau—a US$14.9 billion market in 2009, shared between six concessions—that LVS at The Venetian Macao managed to produce EBITDAR margin of 30.6% in the fourth quarter of 2009, despite a year-on-year fall in receipts from its hotel rooms of 11.8% and in food and beverage outlets of 14.2%, and only a modest growth (3.6%) in its shopping mall receipts.

Off the casino floor

|

So where will the supporting revenue streams for the Singapore casino industry come from? Two of the much-vaunted sources (aside from the luxury hotels at both resorts) are the Universal Studios theme park at Resorts World Sentosa (RWS), and the meetings, incentives, conventions and exhibitions (MICE) trade at both RWS and Marina Bay Sands (MBS).

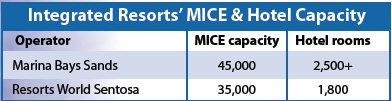

But RWS and MBS are between them only adding around 4,300 hotel rooms to the Singapore market, yet are claiming they can increase Singapore’s daily MICE attendance capacity by 80,000.

Do those two sets of figures stack up when it comes to building Singapore’s MICE sector? It certainly seems unlikely that the injection of a modest amount of hotel capacity in tandem with a major increase

in MICE capacity is going to do much to bring down Singapore’s high hotel room prices. In January this year the average daily room rate (ADR) in Singapore stood at S$187 (US$137). Macau’s ADR for January 2010 was 1,044 patacas (US$130). The Las Vegas ADR for that month was US$99.75.

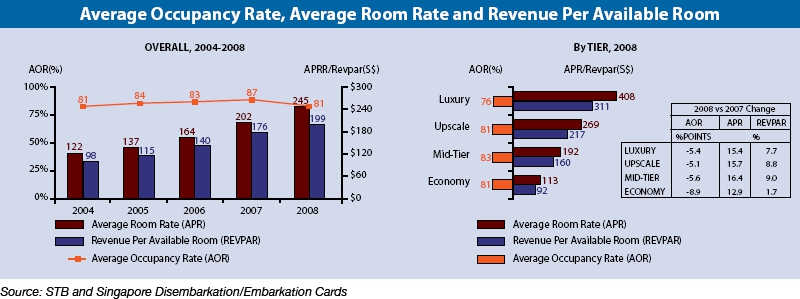

The cost of hotel accommodation is likely to have been a factor in the relatively shallow growth curve of Singapore’s MICE business between 2004 and 2008.

Given the massive potential capacity at the new IRs for MICE attendees compared to their hotel room inventory, it’s likely that on site rooms during conference times will attract a premium, while many conference attendees unable or unwilling to pay a premium will have to stay off site. That kind of pattern has already been seen in Singapore’s existing MICE market.

In March 2008, the travel industry publication Travel Trade Gazette Asia ran a story investigating why in some months Singapore had very strong business visitor numbers, but no corresponding hike in the average occupancy rate (AOR) of its gazetted hotels.

It gave, as an example, July 2007, when Singapore had 25,000 business visitors—one of the highest numbers recorded in a single month up to that time. So why didn’t these 25,000 in theory ‘highyield’ business visitors help boost the AOR of gazetted hotels that month? In fact, the AOR remained at July 2006 levels.

A person responsible for organising accommodation at one of the July 2007 MICE events in Singapore told the publication: “We did not understand the profile of the delegates…To be honest, we over committed to [four- and five-star] hotels. In the end, we could not deliver the numbers.

“Some delegates were willing to pay for rooms in these hotels. But most, who were footing their bills for the trip, were not. These cost-conscious delegates did not book rooms through us; they went directly to three- or even two-star accommodation.”

Many delegates to Las Vegas conferences also find accommodation off site, but that’s common because most of the major properties on the Strip are clustered together. In Singapore, any conference attendees at MBS staying off site will have a short journey from downtown Singapore (typically 11 minutes and a S$7.50 taxi fare at 8.30am, according to the fare calculator taxisingapore.com). But conference attendees at RWS will have considerably longer journeys. A taxi from Orchard Road in the centre of downtown Singapore to Sentosa Island isn’t expensive—about S$14 (US$10)—but at 8.30am on a weekday, will typically take about 25 minutes.

Minister Lim’s assumption that giving more people more reasons to come to a destination will increase the size of that market seems a reasonable one. There are, though, some structural issues in the Singapore real estate market that could create a lack of correlation between the introduction of casinos and the growth of the local MICE market.

What Minister Lim didn’t say in his statement was that some conference and exhibition organisers have been put off Singapore by the relative scarcity and expense of the city’s international standard hotel rooms.

Room premium

|

In March 2006, the Singapore Tourism Board ran a story on its website with the following editorial comment: “Bulk buyers such as tour operators and MICE customers have voiced concern that they are unable to get their room allotments from hotels, and where hotels are willing to commit rooms, they come with a higher price tag and this, they say, could affect demand for Singapore.”

Sim Beng Khoon, Director of Travel and Hospitality Business for the STB, said in response at the time: “If the situation is prolonged, then it could potentially impact demand. Tour groups could opt to go elsewhere or meeting planners could move their events out of Singapore.”

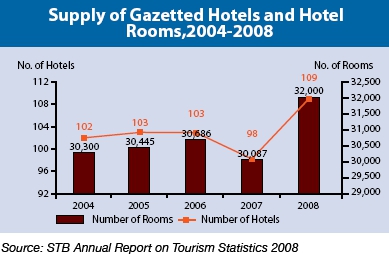

Between 2004 and 2006, only 386 rooms were added to Singapore’s inventory of gazetted hotel rooms (from 30,300 to 30,686). That’s an increase of only 1.3%. Yet during that same period, the annual number of tourist arrivals increased by 21%, from 26.7 million to 32.3 million.

In 2007, the number of available gazetted hotels in Singapore (i.e. hotels excluding small guest houses and serviced apartments) actually went down (from 103 hotels to 98 hotels), and the number of available rooms fell by 601. This was due to a combination of factors: refurbishment of existing properties and demolition of others as a by-product of the better rental yields available to developers from office buildings.

The government tried to solve this hotel room supply problem in 2007 by zoning extra land for hotels and offering it to developers under the Government Land Sales Programme (GLS). The developers, for the most part, said ‘no thanks’.

In that year, eight of the ten land plots designated for up to 5,850 extra hotel rooms under the GLS were rejected by developers and carried over unsold to 2008. Of those, six were vacant and available for immediate development. The reasons cited in the industry for the low take up were the undesirable location of some sites, timing risk and credit availability.

Superior returns on office blocks

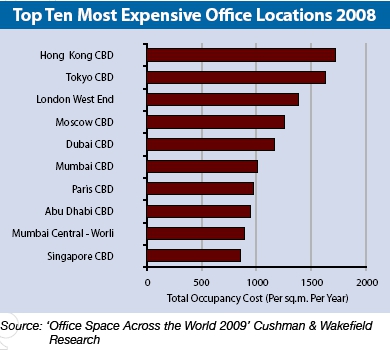

It’s not surprising Singapore developers said ‘no thanks’ to building more hotels. For years, Singapore property values have been overwhelmingly driven by the office sector. The city-state remains one the top ten locations in the world for office occupancy cost. In 2007, it was one of the world’s top five performers in office rental growth with a 78% increase year on year, according to Cushman and Wakefield Research.

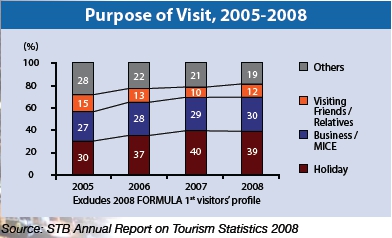

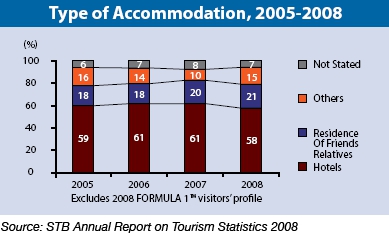

According to Singapore Tourism Board statistics for 2009, the city had on average 26,523 tourist arrivals per day, served by a maximum of 32,709 gazetted hotel rooms at year-end. That’s 1.2 hotel rooms per visitor per day. But only around 58% of Singapore tourists (15,383 per day) actually stay in gazetted hotels, according to the STB. Around 21% stay with friends and family.

That changes the ratio to a much more favourable 2.1 gazetted hotel rooms for every tourist arrival actually seeking hotel space. Were, however, an additional 80,000 daily MICE visitors and 4,300 new hotel rooms from the Singapore IRs to be added to the mix, that would produce a total of 106,523 visitors per day effectively competing for access to only 37,009 hotel rooms of international standard. That’s only 0.3 rooms per visitor.

Singapore has—possibly because of the high cost of its international standard hotels—a lot of small guesthouses. These establishments are known as ‘non-gazetted’ hotels and add another 8,620 rooms to the city’s inventory. But they’re hardly the sorts of hotels likely to attract MICE visitors. Convention delegates don’t normally stay in guesthouses or share a room—at least not with their fellow delegates.

Las Vegas had an average of 99,593 visitors per day in 2009 served by 148,941 rooms at year-end—the equivalent of 1.5 rooms per visitor per day.

Macau had an average of 59,596 visitors per day during 2009 and 19,216 rooms at year-end—an average of 0.3 rooms per visitor. More than half of Macau’s visitors during 2009, though, were daytrippers—11.35 million of the 21.75 million total arrivals for the year, according to DSEC, the city’s statistics and census service.

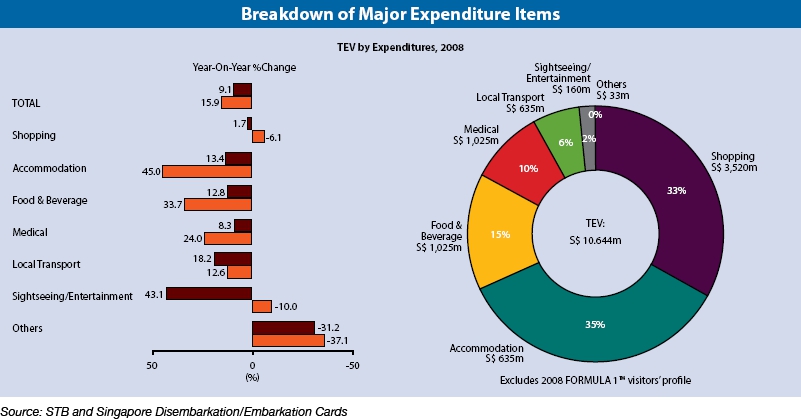

For the first time in 2008, total expenditure of visitors (TEV) on hotel accommodation in Singapore exceeded their spending on shopping. According to the Singapore Tourism Board, that was principally a function of high room rates.

Preferred guests

If Singapore can’t easily increase its room inventory (in the manner of Las Vegas) because of a shortage of space and market competition from other higher yield real estate, it had better move its visitor profile upmarket in order to achieve a better ‘yield’ per hotel visitor. Part of the rationale of the Singapore government in introducing casino gaming appears precisely to have been to encourage elasticity in consumer demand for Singapore hotel rooms in the face of price increases. In other words, the thinking is that MICE bookers and would-be delegates who were previously put off Singapore because of cost will feel compelled to come if casinos are part of the mix.

But is casino gaming Singapore-style the most appropriate ‘trap’ to catch these kinds of high value visitors? That question has been made more pertinent by the decision of the Casino Regulatory Authority effectively to regulate VIP junkets out of the market.

Some anecdotal evidence so far from Resorts World Sentosa has been that many casino users—perhaps the majority—have been mass-market customers from Malaysia and Indonesia. Once the first set of official numbers is out, we will have a better picture of just who is coming.

One obvious way to monitor the relationship, if any, between casinos and the MICE market would be for the Singapore Exhibition & Convention Bureau to include a question on the relationship between casinos and MICE booking decisions in its market research.

Short stayers

Short stayers

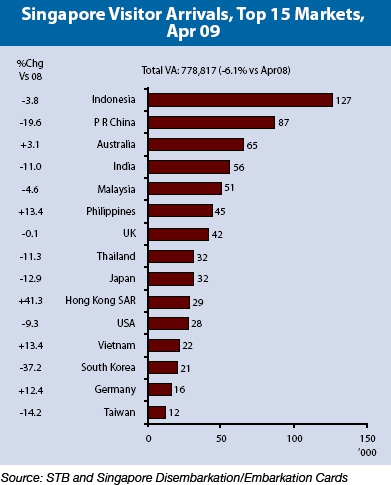

Using April 2009 visitor arrivals as a snapshot, there’s evidence that currently many of the nationalities Asian casino operators think of as their target customers are not staying in Singapore hotels. Out of 778,817 tourist arrivals in April 2009, nearly half came from just four countries, according to STB data. They were: Indonesia (126,797); the People’s Republic of China (86,522); India (55,985) and Malaysia (51,262).

There appears to be a correlation between proximity of those visitors to the market and length of stay. The nearer they live to Singapore, the more likely they are to be part-day or one-day visitors.

Of the Indonesian visitors in April 2009, 30.6% stayed for fewer than 24 hours, 18.5% stayed for one whole day, 15.9% stayed two days and 12.3% stayed three days. With the Malaysians, 44.6% were in town for fewer than 24 hours. A total of 21% stayed for one day, 13.9% for two days and 8.4% for three days.

With the Chinese visitors, 32.7% were in town less than one day, 43.3% stayed for one day, 5% stayed for two days and 4.5% stayed for three days. Among the cohort of arrivals from India, 16.1% visited for less than one day, 13.9%, stayed one day, 19.6% stayed two days and 16.8% remained for three days.

There’s some insight from the local travel industry regarding the large number of people who stay for less than a full day. One factor quoted is the impact of the fly-cruise holiday trade. In that segment, passengers arrive in Singapore, clear immigration and are counted as ‘arrivals’ for statistical purposes. But in fact they transfer straight to their cruise ship. On return, they are again counted as another ‘arrival’, regardless of whether or not they stay on in Singapore or catch a return flight.

Other visitors are counted as arrivals simply on the basis that they use the Budget Terminal at Changi International Airport dedicated to low cost airlines. Passengers who need to make transfers from the Budget Terminal to another flight must clear immigration, collect their luggage, clear customs, make their way to the main terminal by taking a shuttle bus and check-in again with the respective airline.

These visitors are chalked up as ‘tourist arrivals,’ but do not clock time in Singapore, much less stay at hotels. Singapore also has some international visitors that arrive at its entry ports but then head directly to nearby destinations such as Bintan in Indonesia, which have better hotel room availability and lower rates. These budget travellers sometimes schedule a Singapore city tour on their return leg before flying out of Singapore.

Quantity vs. Quality

Quantity vs. Quality

In a sense, the introduction of casinos can be seen as a no lose situation for the Singapore government. As long as more tourists turn up and spend money, the government gets extra revenue from taxation, regardless of whether they’re gamblers, day-trippers, conference goers or a mixture of all three.

The ‘quality’ of visitors in terms of their spending is arguably more critical to the resort operators, given the constraints the Singapore authorities have placed on the amount of gaming space at the venues and the controls on who is allowed in the casinos (in terms of entry fees for local players and stringent regulatory controls on junkets). It’s likely to be the casino resort operators who will pore over the first official market returns the most keenly.