Last month, Sheldon Adelson made one of the most lavish individual contributionsin the history of US presidential politics. Now,he must decide between continuing to back what appears to be a losing cause,or moving his support to the front-running Republican candidate

In a US presidential election awash in more money than sense, Sheldon Adelson was down about US$11 million as February dawned and wondering whether to press his bets or move to a different game.

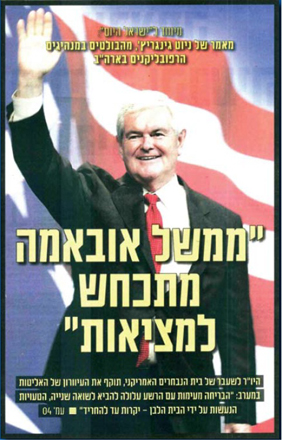

He’d just lost big on former Speaker of the US House of Representatives Newt Gingrich in the Republican primary in Florida, and after his man came up short again in the popular voting to choose Nevada’s delegates to this summer’s nominating convention, either the casino tycoon would be writing another check to a candidacy many see as doomed or shift his bankroll to front-runner Mitt Romney, the polished, square-jawed ex-governor of Massachusetts with the country club tan, the blessing of Wall Street and the Republican hierarchy, and a campaign war chest even the eighth-richest man in the country has to respect.

With seven more states hosting popular votes leading up to 6th March—the biggest day of the campaign, “Super Tuesday” as it’s called, when Republicans in 10 states go to the polls, including Gingrich’s home state of Georgia and a few more Southern states that might be expected to favor him—Mr Romney would like to put this thing away sooner rather than later. He’s sewn up more than 20% of the 1,441 delegates needed for the nomination, and reports last month had it that his camp, which numbers many prominent Jews, had reached out to Mr Adelson.

“There are very few people who think that Romney is not going to get the nomination,” says Nevada political analyst and Las Vegas Sun columnist Jon Ralston. “Sheldon Adelson does read the newspapers, so he knows what the odds are.”

But then it’s never easy to say what Mr Adelson will do. As for the embattled Mr Gingrich, he was telling anyone who would listen last month that he intends to stay in the race to the bitter end, a vow that means almost nothing without his Las Vegas benefactor, who’s been the campaign’s only meaningful source of funds since Mr Gingrich finished a distant fourth in voting to apportion New Hampshire’s delegates in early January (he’d already lost Iowa) and looked to be fading fast, but it does place the billionaire in something of a bind. Mr Gingrich is a friend and a kindred political spirit, a vehement right-winger who stands the strongest for Israel, in Mr Adelson’s view, and shares his patron’s hostility toward organised labour.

“He’s a very loyal guy with those who are his friends, and they have been friends now for quite some time,” says Sig Rogich, a veteran Republican strategist based in Las Vegas.

Of course, it can’t be too far from his mind that Las Vegas Sands Corp (LVS) has been under criminal investigation for the last year by the US Justice Department and the Securities Exchange Commission for alleged bribery of foreign officials in connection with the company’s business activities in Macau, as it has acknowledged in corporate documents.

Ron Reese, Mr Adelson’s spokesman at LVS, did not respond to a request for comment, and Mr Adelson himself has had little to say to the national media that have flocked after him ever since Mr Gingrich pulled out a surprise victory on 21st January in South Carolina with the help of US$5 million from Mr Adelson. It’s the only state he’s won as of this writing. It was on the eve of that vote that Mr Adelson, perhaps feeling a bit more expansive about his investment, issued a statement to The Washington Post: “My motivation for helping Newt is simple and should not be mistaken for anything other than the fact that my wife Miriam and I hold our friendship with him very dear.”

For Florida, a much bigger prize, a crucial swing state with a large and diverse population and 50 winner-take-all delegates, the Adelsons ponied up another US$5 million. But Mr Romney’s people came with US$16 million. A withering enfilade of attack ads sent Mr Gingrich into retreat. He bombed in the lone television debate. When the votes were counted on 31st January, he’d been trounced.

‘The Rules Are Mad’

The non-partisan Center for Responsive Politics estimates that more than US$6 billion will be spent by political parties, campaign organisations, individuals, giant corporations and other special interests looking to place their man in the White House in November and secure a Senate and House of Representatives to their liking. There are legal limits to the amount of the money candidates can accept from individuals in national elections—“hard money,” as this is known—and corporations, labour unions and foreign nationals are prohibited from contributing directly to a candidate. But for as long as there have been limits, there have been big donors seeking influence who found ways to circumvent them. There are so-called “political action committees” (PACs), there are non-profits for the purpose of issues advocacy, the “bundling” of lots of small contributions into big ones, and unregulated “soft money” donations to political parties. In 2002, Congress closed the soft money loophole and moved to rein in the PACs with additional reporting requirements and limits on their activities. Then in 2009 and 2010, a series of federal court rulings were issued that turned the rules on their ear by recasting campaign finance reform as a constitutional discussion about freedom of speech. Throwing decades of judicial precedent out the window, these rulings effectively dismantled the legal basis for spending limits and in the process extended an invitation to those with the deepest pockets — corporations, labour unions, super-rich individuals—to enter the system with as much money as they like.

“The bottom line is that it creates the potential for one person to have far more influence than any one person should have,” said Fred Wertheimer, head of Democracy 21, a group that monitors election spending.

It has summoned into existence a new breed of political beast, the “Super PAC,” which can accept unlimited contributions and spend unlimited amounts to support or oppose candidates as long as it remains independent of their campaign organisations and doesn’t “coordinate” its activities with them—a meaningless distinction if ever there was one, as FEC Commissioner Ellen Weintraub has observed. “Super PACs are functioning as alter egos of the candidates’ committees,” she stated, “and are being run by their friends.”

The Super PACs spent more than US$80 million on the 2010 mid-term elections, according to the non-profit news site ProPublica, and were instrumental in recapturing the House of Representatives for the Republicans. In the current electoral cycle they have amassed more than US$98 million to date.

Laying into perhaps the most controversial ruling (by the US Supreme Court in Citizens United v. Federal Election Commission) that unleashed the Super PACs, Justice John Paul Stevens wrote in a ringing dissent that the ruling “threatens to undermine the integrity of elected institutions across the nation.” Mr Wertheimer called it “the most radical and destructive campaign finance decision in Supreme Court history.”

Enter Sheldon Adelson, a billionaire 20 times over with a long history of putting his money where his mouth is when it comes to bankrolling right-wing causes. Freedom’s Watch was the one that got him the most notoriety. With ties to the Republican Jewish Coalition and then-Vice President Dick Cheney, it was formed in 2007 for the initial purpose of drumming up support for the Bush administration’s plans to step up the war in Iraq, which was going badly. This expanded into ads urging an attack on Iran; a Cheney obsession. But Americans had thoroughly soured on military adventures in the Middle East by then, and the group’s focus shifted to pushing for Republican candidates for Congress, which got it into some hot water under the election rules of the time. Then the credit crisis hit, and with LVS fighting for its corporate life, Mr Adelson had other things on his mind. Freedom’s Watch disbanded after the Democratic landslide in 2008.

Depending on how much he ultimately spends in the 2012 presidential race, it won’t be surprising if he becomes something of a lightning rod once more as calls for electoral reform become more vocal in the wake of Citizens United.

But in fairness to Mr Adelson, it’s the system that has handed him the keys.

Noah Feldman, a constitutional law expert at Harvard University, put it succinctly in a recent interview in the British newspaper The Guardian: “It is an arms race of money. You can imagine a world where you can’t get elected without the backing of a billionaire. Mr Adelson is not breaking any rules. But the rules are mad.”

|

|

‘Newt World’

The story is they first met in Washington in the mid-‘90s when Mr Gingrich was riding high as speaker of the House and leader of the “Republican Revolution” that ended 40 years of Democratic dominance in the lower chamber and Mr Adelson was lobbying for passage of a bill to move the US embassy in Israel from Tel Aviv to Jerusalem, which Mr Gingrich supported. The measure sailed through Congress, but every president since Clinton has refused to implement it. Mr Gingrich says he will.

Later, when Mr Adelson was building The Venetian in Las Vegas and fighting to keep the Culinary Union out of his resort and its pickets off the sidewalks in front of it (which he claimed to own), he tried to have them arrested, and when the police refused, Mr Gingrich dropped in during a fundraising tour to lend support. Mr Adelson would lose the battle for the sidewalks, but he won a victory in the Nevada Legislature with a law forbidding labour organisations from spending members’ dues on political activities. The Venetian and Palazzo are still non-union.

Says Mr Rogich, “They share a common support for the causes that are important to each other, and they have continued to share that over the years.”

In certain ways they are very much alike. Restless, impatient, intensely combative, they both thirst after greatness. Both are enamoured of the bigness of an idea, and their lives have unfolded as a relentless battle against the conventional minds that would thwart their ambitions. In Mr Gingrich’s case, it wasn’t the Democrats that brought about his downfall in Congress; it was his own party. But then both men perceive enemies everywhere; or rather, it seems they avidly pursue them, like warriors who take pride in displaying the scars inflicted by those they’ve slain. It inspires them to see themselves as the underdog. It feels heroic. It’s a crowded self-image. A rebel and a bulwark exist there side by side, a builder and a destroyer. Much as Mr Adelson sees himself as the father of modern Las Vegas, Mr Gingrich sees the conservative movement in America as the child of his singular vision. Which makes them watershed figures in their view, and both seem obsessed with cementing a place in history; Mr Adelson with architectural monuments that command the labour of thousands and cost billions, Mr Gingrich with a complex and overlapping network of businesses and nonprofits encompassing books, collectibles, DVDs, broadcast media, schools, think tanks and high-priced consulting services— Gingrich Communications, Gingrich Productions, Newt.org, the Gingrich Group, and more—a sprawling octopus of self-promotional tentacles that he and wife No. 3, a former congressional aide 23 years his junior, affectionately refer to as “Newt World”. Mr Adelson would pour more than US$7 million into the principal arm of Mr Gingrich’s political machine between 2006 and 2010. Organised as a non-profit, it would burn through US$52 million before it was disbanded last year when Mr Gingrich left it to run for resident.

As the Post noted, “Perhaps no other major presidential candidate in recent times has had his fortunes based so squarely on the contributions of a single donor, as Gingrich has on Adelson.”

Business vs. Friendship

As one of the states hardest-hit by the recession and the collapse of the housing market, the Florida primary exposed the gaping holes in Mr Gingrich’s appeal. His talent for expressing broad principles and grand themes—and he does have a flair for rhetoric—plays well among certain segments of the ultra-right, but he is vague and erratic on bread-and-butter issues and comes off as undisciplined intellectually. And he’s a man with a past. He was slapped with scores of ethics charges during his five years as speaker of the House of Representatives and ultimately was reprimanded by the chamber and fined for violating federal tax law. A political liability at that point, his fellow Republicans had to wrestle the speaker’s chair from him, and in 1999 he resigned his congressional seat in a fit of pique, his public image in tatters. He has never held elected office since and never has regained broad support within the mainstream of the party. Trailing more baggage than Marley’s Ghost, he was vulnerable in Florida when Romney slammed him for influence-peddling in connection with the big fees he collected from a government-sponsored mortgage giant that was disgraced in the housing crisis. Nearly half of Florida’s home mortgages are underwater, and the rate of foreclosures is sixth-highest in the nation. But then Mr Gingrich’s talk of colonies on the moon hardly could have endeared him to voters in a state with 10% unemployment. And there are a couple of jilted ex-wives who refuse to go quietly, and this has bruised him to some extent with women voters and hasn’t helped him with the “family-values” crowd and fundamentalist Protestants, a core Republican constituency that isn’t too crazy either about his close ties to a gambling boss.

If Florida was the beginning of the end for him, and that’s the consensus of the experts, how long will it be before business and friendship part ways?

“That’s a good question,” Mr Ralston says, “whether [Mr Adelson] is going to continue to fund a losing campaign or whether he’s not. I think he’ll wait and see what happens. My guess is that Gingrich will ask him, or someone close to Gingrich, will ask him for more money.”

If anyone had some insight into Mr Adelson’s thinking last month it was a wealthy Texas venture capitalist and lobbyist named Fred Zeidman. He serves as vice chairman of the Republican Jewish Coalition, whose board includes Mr Adelson, and he heads the US Holocaust Memorial Council, a favourite recipient of the casino owner’s largesse, and he’s a friend, and he’s strong for Romney. Speaking just before the Nevada caucuses, he told The New York Times that “Sheldon is committed to keeping [Mr Gingrich] in the race as long as he wants to stay in.”

Published reports have it that Mr Adelson also has assured the Romney camp that they can count on his chequebook when the time comes.

He will not be distracted from the “overriding issue,” Mr Zeidman said, “which is beating Barack Obama.”

Alarm Bell

Alarm Bell