Whether casino operators like it or not, China has the final word on the future of Macau’s gaming industry.

By Steven Ribet, Managing Editor,

“The notion that a person who spent two and a half billion dollars would not know how many tables they are going to have three weeks before they open is so preposterous that it is worthy of comment … The table cap is the single most counterintuitive and irrational decision that was ever made.”

Thus Steve Wynn last October lashed out at the policies of the Macau government and by extension China. The Chairman and CEO of Wynn Resorts was speaking in a conference call following a 38% drop in Macau revenues reported in his company’s third quarter earnings announcement. Whether or not he was merely talking for the benefit of his shareholders, Wynn’s criticisms would have found sympathy among a minority in Macau’s gaming industry, who see table restrictions as part of an overall policy agenda from Beijing that is hostile towards the city.

Yet Wynn’s words were ill chosen, because China holds all of the cards in deciding the fate of gaming in Macau. Moreover, when it comes to the city’s casino industry, at least, the behavior of China’s central government has been both reasonable and rational.

China’s levers of control

Fair behavior or not, attacking China is always a bad idea because the motherland has so many channels of influence over Macau. Take, for starters, immigration. Mainland tourists account for over two thirds of arrivals in the city and just over 90% of visitor spending. Every citizen leaving the People’s Republic, for Macau or any other destination, must apply for and be granted an exit visa.

“China has significant control in terms of its capacity to shut off the faucet, or at least turn the pressure down,” says David Green, principal of the regulatory, market and taxation advisors Newpage Consulting. “From time to time, it has tightened the screws on visas. I think this reflects on the fact that Macau hasn’t really succeeded in extending its appeal to gamers far beyond Greater China.”

China responded after the SARS epidemic scared international tourists away from Macau and Hong Kong, by introducing its Individual Visitation Scheme (IVS). The July 2003 measure allowed Chinese from cities most likely to feed visitors to Macau or Hong Kong to visit either city as individuals instead of in hitherto compulsory tour groups, giving a much-needed boost to both economies. It was only intended as temporary, but has not yet been revoked. Indeed, from 2003 to 2007 more and more cities were added. The number of cities whose citizens are eligible for the IVS now totals 49.

More recently, after Labor Day protestors rioted in Macau in 2007, China slowed down its visa approval process. The move was made without consulting Macau’s government, and was seen by some as pressure on the former territory to get its house in order. China’s Communist Party values social stability more than anything, perhaps, except keeping itself in power.

Macau’s dependency on cross-border traffic from China will increase with the development of Hengqin island. A Special Economic Zone across the Xi River from Macau, Hengqin is being built up as a service satellite district to the city, with hotels and facilities for entertainment, conventions and leisure. In the future it will fall under the joint administration of Macau and the city of Zhuhai. China will likely move its border controls back from the bridge between Hengqin and Macau to the bridge linking Hengqin with the mainland. After that, not only tourists, but also thousands of workers will be moving freely, every day, between Macau and Guangdong Province.

There is also currency controls; the amount of money the mainland allows visitors crossing over into Macau to take with them. Last September the PRC’s State Administration of Foreign Exchange limited overseas ATM withdrawals to 100,000 yuan per year, down from 10,000 yuan allowed per day with no annual limit. It made the restriction in response to the souring national economy causing capital flight, although in December China took another measure aimed specifically at Macau. This was to clampdown on the widespread use of UnionPay cards to make fake purchases at the city’s pawnshops in order to get around currency restrictions. Nearly all bankcards issued in China are UnionPay cards, making this an effective lever of control.

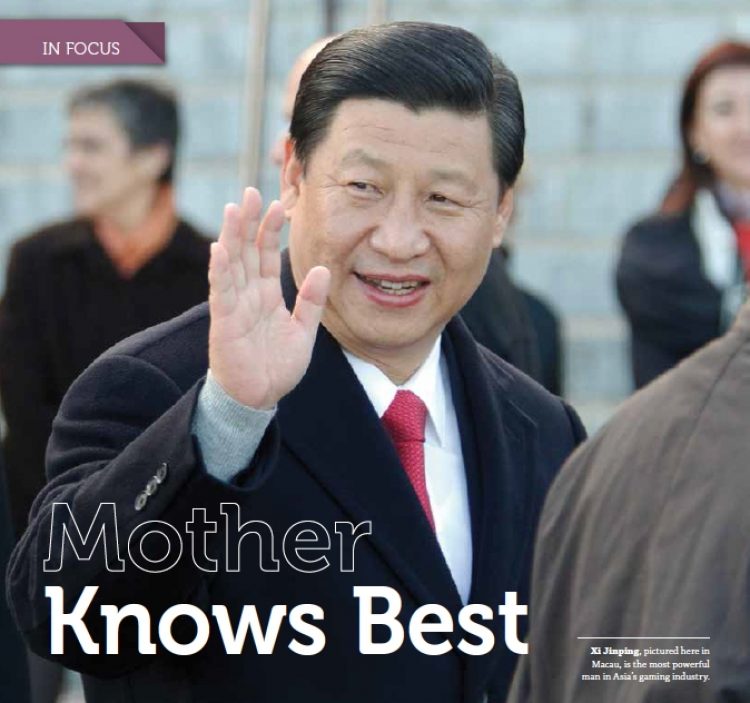

And in addition to visa and currency controls, China can influence Macau’s gaming industry more directly through its say in government policy. China’s State Council appoints the Chief Executives of both Macau and Hong Kong Special Administrative Regions upon recommendation of a local Selection Committee. It also has the power to sack them, as was made plain by the removal of Hong Kong’s first Chief Executive Tung Chee-Hwa in 2005. Last December the structure of power over Macau’s Chief Executive, currently Fernando Chui, was on display when he delivered his annual report to President Xi Jinping in Beijing. Seated at the same table was the Director of the Central People’s Government Liaison Office of the Macao Special Administrative Region, Beijing’s pointman in the city Li Gang. The fourth man at the meeting was Wang Guangya, Director of the Hong Kong and Macau Affairs Office of the State Council, which is charged with formulating policy on Macau.

Inside Asian Gaming made a formal interview request to the Hong Kong and Macau Affairs Office in Beijing, but they did not respond prior to us going to press.

To what extent does Li, and above him Wang, call the shots in consultations with Chui? Chui’s predecessor Edmund Ho in 2008 famously said Beijing had instructed him to halt the construction of new casinos. “Macau is like a typical Chinese city. If there is a policy that Beijing says must be implemented, then the local government has to follow,” says Eilo Yu, Associate Professor at the University of Macau.

The debate about China’s control of the Macau government seems to be more of an academic one, about terminology used to describe that control than whether or not the control is absolute. David Green, for example, prefers to say China exercises “moral suasion” instead of saying it “orders” or “commands.” But he adds, “I can’t recall an instance where Chui has said something contrary to the central government policy line. Under the One Country Two Systems policy it effectively controls what happens in Macau.”

Of course there is more to power in the Macau Special Administrative Region than the Chief Executive and the cabinet he appoints. The Hong Kong SAR shares Macau’s ruling structure. Anti-Beijing legislators and groups in society there often succeed in blocking the government’s agenda. In Macau, however, every political group – from legislators and local business elites to trade unions and charities – can be said to be pro-Beijing. The result is be natural for Beijing to be hostile to Macau’s gambling industry. Other Asian countries including Korea, Vietnam and Singapore have banned or placed heavy restrictions on their own citizens from entering the casinos they allow. They want the pros of allowing casinos, in the form of gaming tax and boosted tourism, without the cons of problem gambling, unscrupulous debt collection and other social issues.

China has it almost the other way around. Macau’s casinos pay no gaming tax to Beijing and they don’t do a very good job of attracting overseas visitors (less than 10% of visitors to the city come from outside Greater China). While the operators have reaped supernormal profits, nearly all of the problems they create have been that in policy, the Macau government nearly always gets its way.

At the Hong Kong Institute of Education, Professor Sonny Lo traces this difference between Hong Kong and Macau back to the riots that blew up in the two colonies during the mainland’s Cultural Revolution. Britain’s colonial government cracked down on the pro-China groups that made trouble in 1967 and dismantled them. So pro-Beijing elements in the colony’s civil society disappeared until negotiations for the transfer of sovereignty in the 1980s allowed them to re-emerge. During Macau’s riots in 1966, however, Mao Zedong forced the Portuguese territory’s weaker colonial government to climb down in the face of rioting Communist Party supporters, and then repress groups loyal to its opposition, the Kuomintang.

“We can say that Macau was from thence on Sinicized, or mainlandized,” says Lo. “While Hong Kong’s executive-legislative relations today are of confrontation, filibustering and continuous disputes, executive-legislative relations in Macau are characterized by relative harmony and smoothness of passage of legislation.”

Macau gaming ; good or bad for China?

Outsiders unfamiliar with Macau’s history and its place as a Special Administrative Region of the People’s Republic might think it would exported to the mainland and, to a much lesser extent, Hong Kong. Gambling aside, the governments of China’s two SARs make no tax contribution to the central government’s coffers; unlike China’s 34 provinces, autonomous regions and municipalities. Even foreign gambling cities like Las Vegas make a contribution to the nation they belong to. For the provision of national defense, then, Macau is getting a free ride.

When China gave the nod to Macau’s 2002 gaming liberalization, it didn’t think the industry would balloon into something seven times the size of Las Vegas, in 2013 making Macau richer than any country in the world (ranked by the World Bank in terms of GDP per capita by purchasing power parity). More than this, it didn’t foresee that Macau’s casinos and banks would become a conduit for corrupt Chinese officials to launder money stolen from China and transfer it into overseas accounts.

“At that time the so-called ‘rise of China’ was just beginning. Beijing didn’t anticipate the rapid growth of China and Macau, and the amount of Chinese money flowing out through Macau, to the extent that in 2013 it would have to set up the National Security Commission to monitor this capital outflow,” says Lo.

The US Congressional-Executive Commission on China’s 2013 report cited a study finding that more than US$200 billion in “illgotten funds are channeled through Macau each year.” Enriched by his huge profits from Macau, Sheldon Adelson has spent hundreds of millions of dollars trying to influence (some might say “buy”) US congressional and presidential elections. This had led some US commentators to remark, wryly, that corruption money from China is corrupting American politics. Chinese academics, meanwhile, say this facilitation of corruption is the only issue important enough to make Macau, with its 0.047% of China’s population, a personal priority of Xi Jinping.

In light of these harms, why doesn’t the mainland set up its own special zones to allow casino gambling say, on Hainan Island or in Yunnan? That way it could keep the gaming revenues for itself and block off a major channel of capital outflow.

Nobody interviewed for this article thinks China would do this. To begin with, the Communist Party fears casino gambling once legalized might run out of control, boosting organized crime and corrupting China’s society and government, perhaps to the extent that opium did in the 19th century. Bruce Kwong, who is an Assistant Professor at the University of Macau’s Department of Government and Public Administration, says deep-rooted ideological objections also figure. “According to the words of Zhou Enlai, gambling is against the very concept of China,” he says.

Historically, Macau developed its gaming industry because it had few other resources to supply its livelihood, no deep-water port like Hong Kong or world-class industries in law and finance. China recognizes this fact of the Macau way of life. “Whether or not you believe the One Country Two Systems policy is being observed, its ultimate purpose is still to act as a model for the reunification with Taiwan,” says Eilo Yu. “If Macau failed it wouldn’t just kill confidence towards the policy inside Taiwan, but also within Hong Kong, which is still very important to China.”

To say Hong Kong is more important to Beijing is not to say that Macau or its prosperity don’t matter. Social unrest in a failed Macau would be a nightmare for the central government. Macau also serves as a diplomatic bridge between China and the lusophonic world; not just Brazil and Portugal, but also Portugal’s former colonies in Africa. Eilo Yu says that Macau’s role as a financial intermediary between China and the outside world, although smaller than Hong Kong, still gains it the protection of Chinese officials.

Lastly, it’s not completely true to say Macau doesn’t contribute financially to China. Every one of Macau’s six gambling concessionaires has now invested in Hengqin, and their billions now account for over half of the island’s stock of capital. The taxes the Special Economic Zone pays after it becomes integrated with Macau will go to China.

China’s problem with Macau

If China wants Macau to prosper and has no intention of ending its gambling monopoly, whence the table limits, and the conflict between operators and regulators they give rise to?

Fortunately, China’s most urgent problem with Macau has already been dramatically reduced. Eilo Yu reckons a ban by China on gambling in Macau for government officials and senior officers in state owned enterprises has been highly effective. He talks about rumors of China’s anti-corruption police placing Macau’s casinos under surveillance, and even hacking into their customer databases. Whether true or not, he says the fear so instilled would scare civil servants from China well away. It’s not clear if the ban will eventually be lifted, or remain in place for good.

As for what China wants from Macau in the long run; it’s been making that clear for years. President Hu Jintao, for example, said the region should be “strengthening and improving the management of the gambling industry, diversifying the economy and lifting living standards,” in a speech made in Macau on the tenth anniversary of its handover. Xi Jinping urged “long-term economic diversification” during his first visit to Macau as Vice President in the same year. He has repeated the message several times since.

In Australia, gambling policy has traditionally been decided at the level of state governments. Separate states started moving ahead to regulate online gaming during the 1990s. The federal government, concerned about proliferation and the potential for damage to be inflicted by operators outside Australia’s jurisdiction, stepped in and used its constitutional powers to pass a countrywide ban.

David Green cites this example to argue in favor of Beijing taking control. “It’s not a case of wanting to put the genie back in the bottle,” he says. “Rather, China is saying, ‘Macau has done unbelievably well out of concessions allowed under the Basic Law. It’s profited from unbridled growth and we’re the ones that have been subsidizing that growth. It’s time for Macau to pull its weight. There should be a real effort to generate attractions and employment opportunities that have nothing to do with non-productive gambling. We need this industry appealing to more than Chinese. Macau has to expand into an international destination.’ ”

Macau’s operators turned a deaf ear to Beijing’s repeated calls, Green adds, until the downturn forced them to start listening. “All you heard from them were comments on the high propensity of Chinese to gamble. They were clamoring for 700 or 800 tables, even though no casino in the world has that many. It was very clear who their target was,” he says. “There was a need to break the cycle. Given the real costs would end up back to China, it made perfect sense for Beijing to act in the way it did.”

“I think the industry did itself a disservice,” says Green. “Until about 18 months ago all you ever heard was ‘how many tables can I get?’ The message the government wanted to hear was not how many tables, but how can I broaden the appeal of Macau by adding to the stock of non-gaming attractions.”

Seen from this point of view, Beijing’s behavior starts to seem less like interference with Macau’s autonomy, and more like prudent management of a potentially dangerous industry.

Of course Xi Jinping will never go on the record to say exactly what he wants to do. Keeping people guessing has always been the Chinese way. But perhaps Bruce Kwong’s opinion is a good approximation of what the paramount leader is thinking.

“Beijing doesn’t want gambling in Macau to grow beyond a certain size, and it doesn’t want an industry that only acts to drain cash from China,” the Macau University professor says. “China will seek to control the development of the gambling industry. China will also seek to develop mechanisms that facilitate this control.”