Macau receives a discomfiting reminder of its violent past

As much as the world has changed for Macau in the last decade, it doesn’t take a lot for those who were here in the bad old days at the turn of the century to recall what it was like when colonial rule, such as it was after 400 years, had disintegrated, and China had yet to assume sovereignty, and open warfare raged among the infamous triads for control of a city rich in vice, the big prize being the lucrative high-stakes gambling rooms of Stanley Ho’s Sociedade de Turismo e Diversões de Macau, which held the monopoly on casinos in the only place in China where casinos were legal.

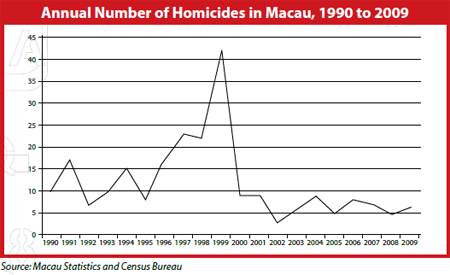

Twenty gang-related murders were reported in 1997, 21 the year before. The violence was so widespread that in an effort to allay the fears of the tourists, General Manuel Monge, under-secretary for security for the Portuguese government at the time, famously quipped that “our triad gunmen are excellent marksmen” who “would not miss their targets and hit innocent bystanders.”

Which proved all too true, as those who attempted to enforce the law were not spared. Victims linked to triad assassins included a customs officer, a gambling inspector and General Monge’s own driver. On 1st May 1998, a bomb exploded under the car of Antonio Marques Baptista, director of the Policía Judiciára. The city had descended into something close to anarchy.

Now and then, whenever the general’s droll words are exhumed, usually it’s as an epitaph on the last days of a dying order, before the arrival of the listed gaming corporations from America and their bigbox resorts aimed at families, shoppers and conventioneers.

That was not the case recently, when in the midst of a rare flurry of mayhem—three murders and a savage assault in the space of a month—they appeared in a New York Times story on the beating of 65-yearold Ng Man Sun, also known as Ng Wai and more popularly as “Street Market Wai,” a casino boss, junket operator and VIP room promoter who came up in Hong Kong’s rough-and-tumble Mong Kok District and holds a controlling stake in the Greek Mythology Casino out on Taipa island, not far from the glittering new Cotai Strip. Mr Ng was set upon on 24th June by a group of armed men in a restaurant in the New Century Hotel, where his casino is located, and worked over so roughly he had to be hospitalized.

A couple of weeks later, in an unrelated crime, two mainland men in their 30s were found stabbed to death in a room at the luxury Grand Lapa Hotel, within sight of Sands Macao, the first of the U.S.-owned, Las Vegas-style casinos that were supposed to have ushered in the new era of corporate legitimacy. A week or so after this, the body of a Chinese woman with a Japanese passport was found in her Taipa apartment. She’d been bludgeoned or stabbed, investigators weren’t sure which.

Asked at that point if violent crime was on the rise in the city, a spokesman for the Policía Judiciára answered as police spokesmen do: that it could not be determined based on two unrelated murder cases.

There are those who disagree, like the security expert who suggested in a Reuters interview that Macau is sliding into a “period of instability”.

“There seems to be a disturbance…amongst the lower end of the junket community,” said Steve Vickers, who served in law enforcement in Hong Kong under the British and now runs a consulting firm there. What’s happening is the stupendous rates of growth that have characterized Macau’s casino market the last few years are on the decline, and those who hold with Mr Vickers see this as part of a potentially dangerous pattern of cause and effect, an unsettling ripple at the edge of a souring world economy that is crimping growth in mainland China, Macau’s principal feeder market, and causing the wealthy there to pull back on their free-spending ways at the baccarat tables. Some insiders say bad debt within the sector is on the rise, debt which is not enforceable under law in the PRC, and the junkets and their affiliated promoters and organizers that bring in the VIPs and provide them credit are facing a liquidity crunch, or a crisis, depending on where they rank on the food chain, and this at a time when they’re all having to compete more aggressively than usual for a shrinking pool of high-net-worth gamblers.

The junkets “operate on a knife edge,” Mr Vickers told The New York Times. “Any disturbance can set off a war between them.”

A ‘Feel-Good Story’

It’s a compelling view for those who remember the bad old days. There is another way to understand the turmoil of the late ‘90s, which is to see it as something that wasn’t unique to Macau at all but was part of a spasm of violence that was region-wide, an outgrowth of the political and economic instability of that time, the growing pains from which modern China emerged. Actually, the bloodshed was far worse in Hong Kong and on the mainland. The tipping point for Macau came in 1998 amid the burning wreckage of Police Director Baptista’s car. The authorities had decided enough was enough, and within hours of the attack the city’s most wanted gangster, Wan Kuok Koi, alias “Broken Tooth Wan,” was arrested in a suite at Stanley Ho’s Casino Lisboa. The flamboyant Mr Wan, who reveled in his role as the reputed leader, or “dragonhead,” of a triad clan known as the 14K and had even commissioned a movie about himself, had appeared in a Time magazine article only a month earlier in which he was photographed posing in front of a Ferrari.

Mr Wan was not charged in connection with the bombing but was tried on loansharking, money-laundering and other offenses, including being a member of a criminal organization, and the following November he was convicted and sentenced to 15 years.

At almost exactly the same time as he was being led off to prison, a less publicized drama unfolded in neighboring Zhuhai, where the Provincial High People’s Court of Guangdong affirmed the death sentence of a Hong Kong gangster named Ye Cheng Jian, alias “Cunning Kin,” for a string of murders and robberies. Thirteen of his co-defendants got prison terms. Kin and two accomplices were promptly taken out and stood before firing squads.

That was a month before Macau’s official repatriation to China, and the message was not lost on the bad guys: This wasn’t Portugal anymore. Step out of line and disturb the peace at your peril.

Today, Macau is one of the least violent cities of its size and unique circumstances in the world. After peaking at 42 in 1999, the number of reported homicides has steadily fallen even as population and visitation have soared. From 2000 to 2009, the city grew 57%, from 350,000 people to 550,000. Ten million visitors came in 2000. Last year, it was more than 28 million. Over this period, reported homicides have ranged from three to nine per year. Atlantic City, a casino town with 40,000 year-round residents and 29 million visitors, had 12 reported homicides last year and 900 reported incidents of violent crime, a rate of 20.7 crimes per 1,000 people. In Macau, with more than 10 times the population, there were four reported homicides and 648 violent crimes, a rate of 1.2 per 1,000.

The triads have done little to disturb the relative calm. If anything they’ve probably been among its guardians—and one of the principal beneficiaries of the prosperity that has ensued by virtue of the intricate ties they enjoy to the junkets and VIP room promoters.

As a former police officer familiar with the industry told Inside Asian Gaming last May, “If you look down the list of licensed junket operators in Macau, sure, you will not find one known triad among them. But I can assure you, none of the big junket operators in Macau could operate unless they were connected to the triads.”

In turn, the junkets have provided the triads with “access to capital,” as one investment analyst has suggested, “and the ability to make money in a manner not previously available to them.”

So they haven’t gone away, they’ve merely availed themselves of the opportunities presented by the new order of things. And with the casinos pumping out cash at levels no gambling market has ever seen, with the government reaping the tax windfall, and the economy humming at full employment, there is little political will to try to root them out “Everyone has enough rice to eat,” as Stanley Ho once put it—which to the Chinese mindset conveys something very close to an ideal state of affairs.

The same analyst said, “I expect that they will evolve into good corporate citizens. There is a lot at stake if they don’t.”

The Grand Lapa, where the two mainland men were killed, is a former Mandarin Oriental hotel, a five-star property whose current owner, Jimei Group, is a Macau-based holding company controlled by junketeer extraordinaire Jack Lam. Jimei has a hand in everything from real estate to financial management to hospitality and tour and travel, cruise ships and casinos in the Philippines and Macau, where it is also a major VIP room operator. Whoever may or may not be connected to these enterprises at various points along the line, certainly the last thing Jimei would want is blood on the carpeting. “No one wants to crash the party,” Ko Lin Chin, a U.S. university professor who specializes in the study of Asian organized crime, told Reuters. “This is a feel-good story.”

The Pending Shake-Out

What then of the crisis in casino revenues? In the anxiety that accompanied May’s numbers, which showed growth of only 7% year on year, few in the investment community were willing to consider that year-on-year comparisons were bound to pale at some point, given the sheer size of the market, and this seems largely to have obscured the fact that May was actually the second-highest-grossing month on record. The gain in June was 12%, but it was below analysts’ estimates and cold comfort for shareholders spoiled by the ethereal gains that have characterized much of the last two years, like the 52% growth posted in June 2011.

Not surprisingly, analysts have lowered their projections for this year. A sampling has Fitch at the low end at 10-12% (down from 15%), Macquarie at 13% (down from 15%), CLSA at 16% (down from 21%).

What we do know is that total GGR is up 19.8% year to date through June. VIP baccarat revenue, the cause of most of the concern, is up 15%.

But there are wealth indicators pointing in the opposite direction as well. May retail sales in Hong Kong grew at their weakest pace since 2009, according to government figures. Luxe brands like Burberry and Prada posted lower gains. Chow Tai Fook, the world’s largest jewelry retailer and a bellwether of how the well-off in China are feeling about life, posted a 16% increase in second-quarter sales, way off the 61% increase recorded in the fiscal year ended in March. Same-store sales were up only 4%. In Macau and Hong Kong, which together account for almost half of Chow Tai Fook’s business, they were about flat at 1%. VIP turnover was down 2.1% year-onyear in June, although some junkets did quite well over that period. To the degree the turnover decline in June is indicative of a downward trend, it’s one the larger networks should be able to ride out. They can reduce their exposure and shore up their books by lending less and tightening up on terms—which they’re doing, according to reports. They can cast a wider net for high-value players. They have the leverage with the casinos to tweak the rules of engagement in terms of the revenue-split and other areas of mutual interest.

Others may not be so fortunate—those at the “lower end,” as Steve Vickers describes them.

But then things can go terribly wrong in Macau even in a booming economy. Just ask A-Max Holdings.

Closely linked with Ng Man Sun, whom it lists at times as an “associate,” at times as a “substantial shareholder,” A-Max was the highflying company that put Altira (then known as Crown Macau) on the map back in 2007 with a unique strategy. It would operate as a junket “aggregator,” locking up several promoters under a subsidiary that would enjoy exclusive run of the casino’s VIP rooms. In exchange for certain guarantees on rolling chip turnover, Altira’s then-fledgling owner, Melco Crown Entertainment, agreed to pay the subsidiary company, which happened to be controlled by Mr Ng, a premium of 10 basis points over the standard 1.25% casinos normally pay the junkets as commission. With the aid of Melco Crown, Hong Kong-listed A-Max raised HK$2 billion on the public markets, the money was plowed into Altira in the form of rolling chips, and the two were in business.

The deal had Street Market Wai’s prints all over it, and it hit Macau’s intensely competitive VIP market like a Molotov cocktail, sparking a rate war that took months to quell and ended only when the other casino concessionaries, as a matter of survival, banded together around 1.25% and prevailed on the government to cap commissions at that rate as a matter of law.

It’s worth noting that what might have happened in the old days didn’t. Not a drop of blood was shed. Not that it did A-Max much good. Its business model promptly collapsed. Melco Crown moved on to other partners, which A-Max claimed was a breach of contract. Mr Ng was to sell off the subsidiary, but no takers were found. A-Max is still trying to recoup some HK$1.9 billion in loans to Altira gamblers.

The company hasn’t fared much better at Greek Mythology, which has been its principal source of revenue. The casino technically is owned by Hong Kong-listed SJM Holdings, Stanley Ho’s post-monopoly operating company, which gets a cut of the revenue in one of those semi-feudal sorts of arrangements that make Western regulators squirm but suit the businessculture of China quite naturally. Jimei’s Grand Lapa operates in a similar fashion. In all there are 20 of these “satellite” casinos in Macau, 14 under the SJM umbrella, six under the other Chinese concessionaire, Galaxy Entertainment Group.

A-Max bought an initial 7.4% stake in Greek Mythology in a deal agreed on in 2004 that cost A-Max a reported US$78 million—$5 million more than the place cost to build. As part of subsequent agreements that had the effect of solidifying Mr Ng’s hold over its destiny, the company later raised its stake to 49.9%. Big things were in the offing at the time. The casino was going to expand to double its size. An entity called Greek Mythology Entertainment Group, with Ng Man Sun listed as president, announced its intention in 2005 to bid for one of the two Singapore resorts. There was talk of investing in Las Vegas and Atlantic City. Over time, it all dissipated like the morning mist in these semi-tropic parts. A-Max learned to its surprise, or so it claims, that its 49.9% was in fact only 24.8%. There had been further maneuverings that saw Mr Ng transfer shares as repayment on a loan from his business partner, a woman named Chen Mei Huan with whom he’d also had two children.

A-Max has attempted to diversify and has moved into lotteries on the mainland. But with more liabilities than assets, and its earnings potential at Greek Mythology slashed by nearly half, it stated its condition in its latest annual report as one leaving “significant doubt about the Group’s ability to continue as a going concern”.

Unabashed, Mr Ng has demanded the removal of the company’s nine directors and their replacement by himself, his daughter and three others of his choosing. Last month, he fired off a letter to that effect from his bed at Hospital Conde de São Januário on Guia Hill, where he is recovering from the injuries he suffered in the attack.

Observers, meanwhile, are talking about a shakeout within the junket community.

“It will more likely be the big guys dominating,” said Hoffman Ma, who heads the company that operates Ponte 16 casino and hotel, one of the SJM satellites.

Neptune Group, the Hong Kong listed parent of one of the city’s biggest junkets, told Reuters it’s looking to acquire VIP room operators. NASDAQ-traded Asia Entertainment & Resources, another prominent junketeer, also expects to be a buyer and said it is considering a dual listing on the HKSE to fund its expansion plans. Reports are that affiliates of SunCity and some other major players might also test the public markets.

Mr Ng and Ms Chen are no longer a pair, having fallen out over their respective rights in Greek Mythology and its host hotel. Or perhaps it’s a love gone sour, as some suggest. In any event, things had been getting increasingly ugly between them in the weeks preceding the attack.

A ‘Beautiful War’

It could be that the thinking in Beijing back at the turn of the century was the junkets would fade in importance once STDM’s monopoly was permitted to expire and outside investment began to transform Macau into a respectable leisure destination. That might have been naïve. There are now upwards of 200 of them, companies and individuals, holding licenses from the Macau Gaming Inspection and Coordination Bureau. A troublesome legacy of the bad old days, perhaps, but they have not only survived into the new era, they’ve also been its mainstay, delivering the high rollers who generate 70% or more of casino revenues, supplying and assuming the risk for most of the credit that greases the wheels, and functioning ultimately as the largest source of government revenue. Something like US$500 billion a year in rolling chip volume passes through these sprawling networks— and, to be sure, their secret partners and investors—and yet the machine has managed to fly smoothly beneath the radar while driving GGR growth from around US$3 billion a decade ago to more than $33 billion, the equivalent of five Las Vegas Strips.

They’ve done it in the teeth of currency and travel restrictions, with no formal banking infrastructure to support them and no system for adjudicating conflicts in civil law. In the process, they’ve been instrumental in sustaining the fortunes of three of the world’s largest publicly traded resort conglomerates. Wynn Resorts, Las Vegas Sands and MGM Resorts International now proudly call themselves Chinese companies, as well they should.

At 91, Stanley Ho, who presided over this world for about as long as anyone can remember, has faded into ill health to leave 17 children and various wives and concubines to squabble over his fortune. As for the likes of Street Market Wai and Broken Tooth Wan, no doubt they’re puzzling over how they fit into the new order.

If it’s true of the man who calls himself Ng Man Sun that he invented the modern junket system with Dr Ho back in the 1980s, then he is in his hospital room now up on Guia Hill, looking down from Macau’s highest point at a city he largely helped create. On that same promontory the policeman Antonio Marques Baptista had gone jogging the day his car exploded in flames.

It appears that Mr Ng, at 65, has no intention of going quietly. His ex-lover bamboozled him, so he claims, persuading him to hand over a controlling interest in the New Century for the promise of a land grant on Cotai that never materialized. Worse, he believes she’s cuckolded him, according to a tabloid story making the rounds in Hong Kong. A recent visitor to his hospital bed reported him morose, uninterested in talking. He has answered his attackers by taking out an ad in the Chinese-language Macau Daily News offering HK$10 million for information on the “mastermind” behind them.

In December, Wan Kuok Koi expects to walk out a free man from a special security wing of the Estabelecimento Prisional de Macau out on Coloane island. He will be 57. It is difficult to imagine that he has lost his taste for the limelight in the years he’s been away. Triad members are said to comprise two-thirds of the male inmates of the Prisional, where reports have it that Mr Wan enjoys female visitors and has use of a mobile phone.

Reputedly a protégé of Mr Ng early in his career, by the late ’90s, they had become bitter rivals. In July 1997, at the height of the triad wars, the front of the New Century was strafed with gunfire. In the interview Mr Wan gave to Time, he spoke at length of their feud, promising to wage a “beautiful war” against Street Market Wai and vowing to “wipe him out”.

Mr Wan’s lawyer, Pedro Redinha, avers that his client has no intention of returning to the life he led before he went away. Moreover, he intends to prove his innocence. “He wants to come to my office to re-examine his case and the grounds for his imprisonment,” Mr Redinha told the South China Morning Post last spring. “I’m absolutely sure he will contact me on his release. He still feels it was an unfair ruling.”

In anticipation, according to a more recent Post report, casino executives are beefing up their personal security.