Looking back to when an industry and a city were set upon a path that would transform them beyond recognition

In 2002, on the 1st of April to be exact, the government of the fledgling Macau Special Administrative Region of the People’s Republic of China formally approved the new casino concessions awarded to Stanley Ho’s Sociedade de Jogos de Macao, Hong Kong-based Galaxy Casino and Steve Wynn’s Las Vegas-based Wynn Resorts.

It was perhaps no more than a matter of administrative housekeeping—the three having been chosen two months earlier, the winners of a global tender that had drawn more than 20 companies and investment groups—but it marked the beginning of Macau’s transformation from the sleepy, seedy gambling town it had been in colonial times—the “Monte Carlo of the Orient” was the generous title appended to it—to a resort destination of worldwide significance; the “Las Vegas of Asia”.

Nothing would be the same again, not Macau, not China, not the global casino industry, which could be said to be truly multinational from that day forward.

When China opened the floodgates The “Individual Visit Scheme” was introduced on 28th July, 2003 to boost economic growth in the repatriated former colonies of Hong Kong and Macau. As the name suggests, it allows travelers from select cities in Mainland China to visit the country’s two self-governing “special administrative regions” on a limited basis as individuals. Previously, this required a business visa or membership in a group tour.

Mainland Chinese are the fuel driving Macau’s red-hot gaming industry, and the IVS is the reason why. The IVS was enacted by the central government in Beijing as a means to offset the impact of the severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) epidemic, which took its toll in the first half of 2003 on the economies of both Macau and Hong Kong, with the latter already reeling from the effects of the Asian financial crisis. Hong Kong was the intended primary beneficiary of the scheme, following an unprecedented street demonstration by well over half a million people there on 1st July, 2003 (the sixth anniversary of the handover of the city to Chinese sovereignty). While the nominal focus of the protest was a proposed anti-sedition bill in Hong Kong, China surmised the city’s economic woes were the real root of the protestors’ dissatisfaction, and the IVS was one of a few economic gifts bestowed by Beijing in response to boost Hong Kong’s economy and appease its population.

While Hong Kong was the targeted beneficiary, Macau and its tourism-dominated economy ended up reaping the biggest gains from the IVS scheme. Coming as it did the year after the first post-monopoly casino concessions were awarded, the timing couldn’t have been more propitious. To give you an idea of its impact, in 1999, the year Chinese sovereignty was restored, the Macau Statistics and Census Bureau counted 1.6 million Mainland Chinese visitors. In 2010, those visits totaled more than 13 million, 53% of all arrivals, and 5.4 million of them, or 41% of all Mainland visitors, made the trip on individual visas. Last year, Mainland Chinese comprised 57% of visitor arrivals, a surge of 17% year-on-year, and individual visas accounted for about 42% of that.

Today, the IVS generates 70% of China’s outbound tourism. Currently, about 270 million residents in 49 cities are eligible to apply, including all 21 cities in Guangdong, the province bordering Macau and Hong Kong and the most populous in the country.

IVS travelers pay dividends outside the casinos too. Because the scheme restricts the frequency and duration of their visits, Mainland visitors tend to stay longer and spend more—MOP2,039 per capita in Macau in 2010 versus MOP1,158 by visitors from other countries—and they constitute more than half of all hotel guests. |

The process of completing the contracts with the concessionaires would extend into June of that year, and as it happened, before the year was out, the playing field would be altered again, dramatically, with the awarding of a separate concession to a second US operator, Las Vegas Sands.

LVS Chairman Sheldon Adelson had been one of the first to recognize the vast possibilities of the market as a play on China’s booming economy. He was wary, however, of taking the plunge on his own, influenced no doubt by Macau’s image as the Wild, Wild East, rife as it was at the time with reports of gangland influence and rival criminal clans jostling for territory, sometimes violently so, in Stanley Ho’s lucrative VIP gambling rooms. Having decided for the sake of his Nevada license and to mitigate his financial risk that it was safer to enter the market as a manager rather than a developer of casinos, LVS found in Galaxy, which had come under the control of Hong Kong construction and property magnate Liu Che Woo, a partner with pockets more than deep enough to handle the capital investment end. But the partnership foundered. LVS’ commitment to the development of Cotai was perceived by many at the time as a risky bet—a view that Galaxy may have shared. In any case, it’s hard to see how it made sense from Galaxy’s vantage that as prospective builder and owner they would have to shoulder the lion’s share of the partnership’s costs and the attendant risks. The government, on the other hand, had bought into Mr Adelson’s singular vision for the reclaimed land between the former islands of Taipa and Colane, and since Galaxy already had a concession, a way had to be found to allow LVS to go forward independently.

The accommodation that was reached, technically a “subconcession” under Galaxy— in effect a fourth license— adn’t been contemplated back in 1999 when concurrent with Macau’s reversion to Chinese rule it was decided to fashion a unique economic identity for the new SAR by opening to international competition a casino market that had been run as the monopoly of one favored company or another since the 1930s. The consequences would prove just as momentous since theoretically the concession holders could develop an unlimited number of properties, subject to government approval, and since the other two concessionaires naturally would expect the same subconcession rights. Which is exactly what happened.

In June 2004, a month after LVS opened the first of the new-competition casinos, the US$265 million Sands Macao, SJM sold its subconcession for $200 million to a joint venture between Las Vegas-based MGM Mirage (now MGM Resorts International) and Hong Kong businesswoman Pansy Ho, daughter of the revered tycoon who had held the casino monopoly for 40 years and still dominated the market as SJM’s managing director. The $1.25 billion MGM Grand Macau would open in 2007.

By 2006 the market had grown so spectacularly that Wynn’s subconcession would fetch US$900 million. The buyers, Stanley Ho’s son Lawrence Ho and James Packer, head of Australian media and gaming empire PBL, would eventually take their joint venture public on the Nasdaq stock exchange as Melco Crown Entertainment. They would open three casinos, among them the US$2.1 billion City of Dreams on Cotai.

LVS would go on to build the US$2.4 billion Venetian Macao on Cotai and invest some $8 billion in the market to date.

The growth of the market in the last ten years, as well-documented as it’s been, is no less amazing in the retelling. The pent-up demand unleashed by the 2004 opening of Sands Macao would blow away the most optimistic projections. The doubling of the number of lead developers to six made certain that capital investment would pour in in sufficient quantities to exploit it. Indeed, the building boom that ensued would see US$13 billion invested in the market in the last five years alone. In addition, Melco Crown, SJM, Wynn, LVS, Galaxy and MGM would all list their Macau operations on the Hong Kong Stock Exchange, raising more than US$6 billion from eager investors, their collective market capitalization today topping US$65 billion.

The industry would grow from 11 casinos in 2002 to 34, an average of two openings a year. The number of table games would increase from 339 to more than 5,300; slots from about 800 to more than 16,000; annual visitation from about 9 million to more than 28 million—spurred by a gradual relaxation of restrictions on individual travel from Mainland China, where disposable income has been growing at an average rate of 10% a year and much higher than that among wealthier segments of the population.

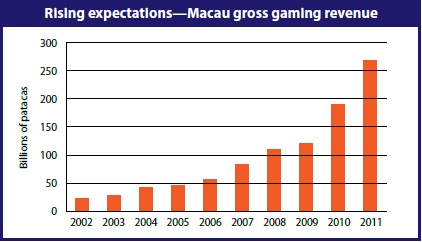

The decade would see Macau’s emergence as the largest pure gambling market in the world. Gross gaming revenue would grow more than tenfold, from MOP22.18 billion, about US$2.93 billion at current exchange rates, to MOP267.86 billion last year, the equivalent of $33.5 billion. That’s five times what the Las Vegas Strip took in in 2011. At 28% per year, the annual rate of GGR growth since 2002 has been roughly twice the rate of GDP growth in China. The S&P 500 has delivered an annualized rate of return of 0.38% over the same period.

VIP baccarat has been the dominant game throughout. It accounted for 74% of GGR in 2002. It dipped to 63% in 2005, a period when the take from the mass-market tables doubled to 23%. It climbed back to 73% in 2011.

Source: DICJ

The years have seen some traditional games fade in importance while others have come from obscurity to become bellwethers of a more diverse and increasingly more mainstream player base. Machine gaming has been the most notable. An insignificant sector in the monopoly days, slot GGR has been growing since 2002 at twice the annual rate of the market as a whole. Last year, the machines generated MOP11.42 billion, good for 4.3% of total revenues. Only baccarat earns more. Stud poker, unknown before 2003, took in MOP1.3 billion in 2011. Texas Hold ‘Em, a MOP54 million game when it debuted in 2008, took in MOP277 million last year. GGR from electronic multi-games has more than doubled to MOP311 million in little over a year.

The changes wrought on society have been dramatic as well. Today, about 15% of Macau’s working population is employed in a casino, more than 22,000 of them as croupiers. Full-time casino workers earn the equivalent in US dollars of $2,090 per month on average, considerably more than workers outside the industry, who bring home a median of between $1,275 and $1,500. But then, before the gaming boom, they would have been fortunate to make $150 a week. Unemployment, which stood at 6.3% in 2002, was 2.1% last year, the fourth-lowest rate in the world (only tiny, oil-rich Qatar and the export-driven states of Thailand and Singapore were lower). Macau’s total working-age population of 347,000 or so can no longer supply the economy’s demand for able, qualified bodies in hospitality, construction and services. The number of non-resident workers has nearly tripled over the last decade, and authorities estimate that 30,000 more imported workers will be needed this year alone to sustain a labour force that could grow by as much as 10% in the next 10-12 months.

But restrictions on foreign workers are a political fact of life, and there is widespread opposition to relaxing them.

It’s a volatile issue. Those who through lack of education or job skills have missed out on the general prosperity have made their discontent known on more than once occasion. Twenty-five police were injured in street protests on May Day 2006. Four demonstrators were arrested. May Day 2007 was worse. A bystander was killed by a stray police bullet. Ten were arrested, 21 police were injured. Government has been treading something of a high wire on this issue ever since, suspended between the desire to encourage investment in Macau’s progress as a leisure destination and the need to temper it while the social infrastructure slowly catches up. In May 2008, then-Chief Executive Edmund Ho announced a short-lived moratorium on new gaming projects and licenses. More recently, a decision to cap the number of new table games at 3% a year has served only to confuse everyone, especially with the government committed to continued large-scale resort development on Cotai.

The rapid pace of development has sparked competitive flare-ups among the casinos as well. At the same time, operators have shown an increasing willingness to work together when confronted with crises that threaten to undermine the health of the industry—like the VIP commission rate war of 2007-08.

“Then in December 2007, Melco Crown’s newly opened Crown Macau (now Altira) threw the market into turmoil by announcing a deal to pay Hong Kong-listed junket promoter Amax a record 1.35% [rolling chip commission]. The effect on margins was so acute that within months the office of the chief executive weighed in with a proposal to roll back the rate to 1.25% and freeze it there by law.”

The standard commission on rolling chip volume in the city’s VIP rooms had been steadily climbing since the end of the monopoly era, when it stood at a manageable 0.7%. By the middle of the decade it was well above 1%. Then in December 2007, Melco Crown’s newly opened Crown Macau (now Altira) threw the market into turmoil by announcing a deal to pay Hong Kong-listed junket promoter Amax a record 1.35%. The effect on margins was so acute that within months the government weighed in with a proposal to roll back the rate to 1.25% and freeze it there by law. By that time, though, under the auspices of the venerable Stanley Ho, the operators had begun meeting regularly to discuss matters of mutual concern. Out of those meetings came Macau’s first casino industry trade association, the Chamber of Macau Casino Gaming Concessionaires and Sub-Concessionaires. When in August 2009 the government finally drafted a regulation to allow for the imposition of a cap, the casinos had already agreed to enforce the recommended 1.25% on their own.

There are other challenges. The city remains largely a day-trip market. Nongambling spend continues to lag far behind spending at the tables and slots. Average length of stay remains about where it’s always been, never moving much beyond a day. A shortage of hotel rooms keeps rates high and discourages casual visitors who tend to spend more and stay longer. Developing the MICE trade is another key. On the plus side, development of Cotai is proceeding apace, the focus there on more expansive resort offerings—more entertainment, dining and shopping for the masses—with several thousand new rooms expected to come on line as more development applications are approved over the next few years. Meanwhile, a number of high-profile road and rail projects are moving ahead that will speed access to the city from Hong Kong and extend its reach even deeper into Mainland China.