Tax regimes for gambling operators in the EU and beyond

As explained in January’s article by April Carr of Olswang LLP, regulation and tax are fundamental issues for gambling operators considering establishing a presence in Europe. January’s article focused on the licensing regimes in the countries that currently permit operators to offer gambling services. This article considers the different approaches to taxation taken by jurisdictions that commonly play host to gambling operators. That said, regulation and tax should not be considered in isolation from each other. Regulatory and tax policies have both shaped the landscape of the European gambling market today and continue to have an impact on operators and their businesses, albeit at times in different ways.

No harmonisation of direct taxes or gambling duties in the European Union

The laws of the European Union (EU) go some way to ensure that companies established in one of the 27 EU countries (Member States) can trade freely in (and offer their services to consumers based in) other Member States. There is, however, little by way of harmonisation of tax laws throughout the EU with the exception of certain EU-imposed taxes such as value added tax (VAT). The imposition of taxes (including direct taxes such as corporation tax, income tax and gambling duties) remains a competency of each Member State. Indeed, the preservation of Member State sovereignty over taxation constitutes one of the major hurdles to a fully harmonised EU.

Gambling operators are typically taxed more heavily than other businesses, paying direct taxes (i.e. corporation tax) on their profits and any social security contribution as an employer, together with specific betting duties and levies. Unlike most other traders (but similar to banks and insurance companies), gambling operators also cannot reclaim the majority of the VAT that they suffer on supplies made to them.

Different approaches

1. Open regulatory but high tax jurisdiction

One might assume that jurisdictions with open regulatory regimes would also seek to attract gambling operators with relatively moderate taxation regimes. This is not necessarily the case.

The United Kingdom (UK) has perhaps the most liberal gambling regime in the EU, permitting online betting for some time and online gaming since September 2007. However, few online operators have established themselves in the UK. The majority of UK-facing online operators have set up or relocated overseas due to prohibitively high taxation levels in the UK. UK-based operators pay 15% general betting duty (or 15% remote gambling duty) on their gross profits and 10% Horserace Betting Levy (‘Levy’) on gross profits from bets on British horseracing. They also pay corporation tax on their taxable profits at between 21% and 28% and employer’s National Insurance contributions (NICs) at 12.8% on the gross salaries and bonuses of their employees and directors (to increase to 13.3% in 2010/11). In addition, their employees and directors will, from 6th April 2010, suffer income tax and employee NICs at rates that, at the top end of the pay scale, will result in them taking home a net amount which is less than half of what they earn gross.

A factor in this ongoing migration has been that the UK currently permits gambling operators licensed in other states within the European Economic Area (i.e. the EU and the European Free Trade Association countries Norway, Iceland and Lichtenstein), plus Gibraltar and certain jurisdictions on a so-called ‘white list’ (Alderney, Antigua & Barbuda, the Isle of Man and Tasmania) lawfully to advertise their services to UK citizens.

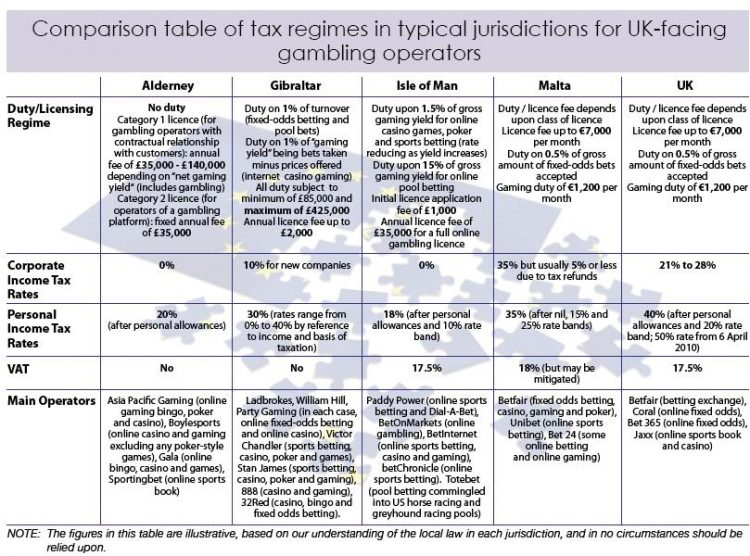

Consequently, the majority of UK-facing offshore bookmakers are now established in one of the following four jurisdictions—Gibraltar, Alderney, Malta or the Isle of Man. From there they can lawfully advertise to the UK public while paying taxes (and not just gambling taxes) at rates that are materially lower than those in the UK. This differential in tax rates is illustrated in the table at the end of this article.

The British government has recently reconsidered these rules with a view to (i) levelling the playing field for UK-based operators of remote gambling operations to enable them to compete with overseas rivals and (ii) securing fair contributions from overseas licensed operators toward the costs of regulation, the treatment of problem gambling and the Horserace Betting Levy. However, the review was criticised for failing to consider the main issue; namely the taxation of remote gambling and gaming companies. In August 2009, the two largest UK-based retail bookmakers, William Hill and Ladbrokes, gave credence to such criticism by both announcing they were moving their respective Internet sportsbooks to Gibraltar.

In January 2010, the British government announced proposals to require offshore operators (from EEA or ‘white list’ states) to hold an additional licence from the Gambling Commission in order to continue to be able lawfully to advertise their gambling services to residents of the UK. The licence would require operators to comply with British technical standards and social responsibility and general regulatory obligations. Crucially, these proposals do not explicitly deal with taxation or the Levy. Under the new regime, overseas operators But these fees (in addition to any local taxes that they are already having to pay) are likely to pale into insignificance when compared to the tax savings achieved from being located outside the UK (especially for those operators with larger turnovers). The UK government has indicated it may keep the ‘white list’ in “some form”, but has not given further details. Until this point is clarified, online operators face a degree of uncertainty

regarding their future operations. Yet it is inconceivable, with an election due to take place in the UK no later than June of this year, that the UK government will find the time both to finalise these proposals and enact the necessary legislation.

2. National licensing system with taxing rights

Several EU Member States are currently proposing to introduce a national licensing system for remote gambling that, in many cases, is to be underpinned by blocking mechanisms to halt financial transactions and/or deny Internet access to unlicensed gambling websites. These plans are generally founded on a desire that, to be able lawfully to offer gambling services in a Member State, operators should also be registered, and pay taxes, in that same State. This clearly raises European law issues, particularly questions concerning the principles of the freedom of establishment and the freedom to provide services. Some Member States have attempted to oblige remote operators to be established within their jurisdiction. That’s with a view to bringing the operators within the direct tax net such that their profits are subject to corporate income taxes in that Member State (in addition to any local gambling duties). To date, the European Commission has not permitted Member States to operate such licensing systems, having scrutinised both the Italian and French systems on such grounds.

In contrast to the Commission’s approach to date, the European Court of Justice (ECJ) ruled last year that Member States may restrict remote gaming operators established in other Member States from operating and advertising in that Member State on grounds of protecting national consumers against potential fraud and crime. Despite the ECJ’s recent support for Member States taking a more restrictive approach, however, the trend in a number of key EU Member States is towards a degree of liberalisation of regulatory and tax policies.

France has historically maintained a strict state monopoly on betting (including betting on horse racing) and lotteries. The Commission opened an infringement procedure in June 2007 against France to verify whether its national measures, preventing the cross-border supply of online gambling services, were compatible with EU law.

In 2009, France introduced proposals to open up its online gambling market but only in relation to certain products, namely sports betting (including pool betting on horse racing) and poker. Assuming such proposals are adopted, operators from outside of France could apply to be licensed in France (with licences held in other Member States being taken into account but not guaranteeing the issue of a French licence). French licensed operators would have to maintain websites containing the “.fr” country code top level domain name and the relevant IT infrastructure (server) would have to be located in France and duly approved by the regulatory body. It is proposed that tax would be levied on stakes placed by customers at the rate of 7.5% for horserace and sports betting and at the rate of 2% for poker games. Specific levies would also be applied to all gambling and betting transactions at the additional rate of 1% (rising to 1.8% in 2012) payable by licensed sport operators (to fund the National Centre for the Development of Sport) and of 8% on horserace betting (to fund the French racing industry). Gambling companies incorporated in, with their place of effective management in, or carrying on operations (presumably through a permanent establishment) in, France would also have to pay corporate income tax at the headline rate of 33.3%.

Italy proposes to introduce new remote gaming and licensing rules (which have received the Commission’s approval) that are less restrictive than those currently proposed by France. In order to qualify for an Italian remote gaming licence, operators would have to be licensed and established within an EEA State and have a permanent link-up with the AAMS (the Italian licensing authority) centralised system for compliance, monitoring and tax purposes.

Historically, Italian tax was levied on online fixed odds sports betting at a rate of 3% of turnover on single bets and 5% of turnover on multiple bets. Together with proposals to introduce remote casino and poker-type games into the Italian licensing system, recent proposals have been made to change this basis of taxation to a tax at the rate of 20% of gross profits (essentially stakes less winnings) on most remote betting and gaming. However these proposals have not yet been enacted.

Gambling companies incorporated, or with a permanent establishment, in Italy are subject to Italy’s corporate income tax, which is currently levied at the rate of 27.5%. Gambling companies must also pay a regional tax of between 2.98% and 4.82% depending on the region in which they are established.

3. Outdated licensing system with low tax rates

Ireland’s licensing system is far behind that of other EU Member States in simply not providing a regulatory framework for remote gambling or gaming operations. In addressing this issue, it is currently unclear whether Ireland will pursue an approach similar to that of the UK, which adopts the concept of mutual recognition of EU gambling operators, or whether it will follow the growing trend of jurisdictions such as France and Italy and impose a local licensing system and restrict access for operators without a domestic licence.

Direct tax rates in Ireland remain low, being levied at 12.5% on Irish trading income. Betting tax is currently levied at the rate of 1% of turnover. Despite relatively reasonable tax rates, however, the major Irish-facing online and telephone operators, such as Paddy Power and Boylesports, have established their remote operations offshore. It is understood that the decision of the Irish Government to defer the proposed increase in the rate of betting tax to 2% of turnover was partially driven by a desire to tempt such businesses back to Ireland.

Author: Stephen Hignett, Partner and Natalie Coope, Associate, Olswang

Olswang is a full service European law firm specialising in the gambling, media and technology sectors. Stephen and Natalie both provide UK tax advice for clients in a wide range of industries including the gambling and media sectors. stephen.hignett@olswang.com natalie.coope@olswang.com